Pro-democrcacy protests continue in Hong Kong and not going to stop soon.

The protests began in June over plans – later put on ice, and finally withdrawn in September – that would have allowed extradition from Hong Kong to mainland China. But they’ve now spread to reflect wider demands for democratic reform.

This is not all happening in a vacuum. There’s a lot of important context – some of it stretching back decades – that helps explain what is going on.

Hong Kong has a special status

It’s important to remember that Hong Kong is significantly different from other Chinese cities. To understand this, you need to look at its history.

It was a British colony for more than 150 years – part of it, Hong Kong island, was ceded to the UK after a war in 1842. Later, China also leased the rest of Hong Kong – the New Territories – to the British for 99 years.

It became a busy trading port, and its economy took off in the 1950s as it became a manufacturing hub.

The territory was also popular with migrants and dissidents fleeing instability, poverty or persecution in mainland China.

Then, in the early 1980s, as the deadline for the 99-year-lease approached, Britain and China began talks on the future of Hong Kong – with the communist government in China arguing that all of Hong Kong should be returned to Chinese rule.

The two sides reached a deal in 1984 that would see Hong Kong return to China in 1997, under the principle of “one country, two systems”.

This meant that while becoming part of one country with China, Hong Kong would enjoy “a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs” for 50 years.

As a result, Hong Kong has its own legal system and borders, and rights including freedom of assembly and free speech are protected.

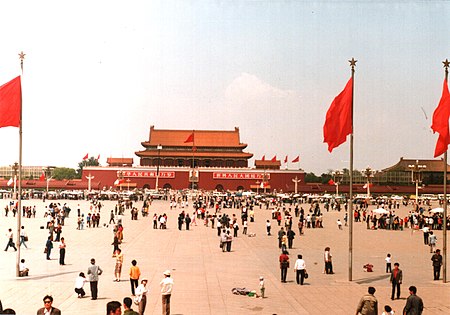

For example, it is one of the few places in Chinese territory where people can commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, where the military opened fire on unarmed protesters in Beijing.

What is Tiananmen Square crackdown?

The Tiananmen Square Crackdown, commonly known in mainland China as the June Fourth Incident were student-led demonstrations held in Tiananmen Square in Beijing during 1989. The popular national movement inspired by the Beijing protests is sometimes called the ’89 Democracy Movement. The protests started on April 15 and were forcibly suppressed on June 4 when the government declared martial law and sent the military to occupy central parts of Beijing. In what became known as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, troops with assault rifles and tanks fired at the demonstrators and those trying to block the military’s advance into Tiananmen Square. Estimates of the death toll vary from several hundreds to several thousands, with thousands more wounded.

Things are changing now

Hong Kong still enjoys freedoms not seen on mainland China – but critics say they are on the decline.

Rights groups have accused China of meddling in Hong Kong, citing examples such as legal rulings that have disqualified pro-democracy legislators. They’ve also been concerned by the disappearance of five Hong Kong booksellers, and a tycoon – all eventually re-emerged in custody in China.

Artists and writers say they are under increased pressure to self-censor – and a Financial Times journalist was barred from entering Hong Kong after he hosted an event that featured an independence activist.

Another sticking point has been democratic reform.

Hong Kong’s leader, the chief executive, is currently elected by a 1,200-member election committee – a mostly pro-Beijing body chosen by just 6% of eligible voters.

Not all the 70 members of the territory’s lawmaking body, the Legislative Council, are directly chosen by Hong Kong’s voters. Most seats not directly elected are occupied by pro-Beijing lawmakers.

Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the Basic Law, says it should ultimately both the leader, and the Legislative Council, should be elected in a more democratic way – but there’s been disagreement over what this should look like.

The Chinese government said in 2014 it would allow voters to choose their leaders from a list approved by a pro-Beijing committee, but critics called this a “sham democracy” and it was voted down in Hong Kong’s legislature.

In 28 years’ time in 2047, the Basic Law expires – and what happens to Hong Kong’s autonomy after that is unclear.

Most people in Hong Kong don’t see themselves as Chinese

While most people in Hong Kong are ethnic Chinese, and although Hong Kong is part of China, a majority of people there don’t identify as Chinese.

Surveys from the University of Hong Kong show that most people identify themselves as “Hong Kongers” – only 11% would call themselves “Chinese” – and 71% of people say they do not feel proud about being Chinese citizens.

The difference is particularly pronounced amongst the young.

“The younger the respondents, the less likely they feel proud of becoming a national citizen of China, and also the more negative they are toward the Central Government’s policies on Hong Kong,” the university’s public opinion programme says.

Hong Kongers have described legal, social and cultural differences – and the fact Hong Kong was a separate colony for 150 years – as reasons for why they don’t identify with their compatriots in mainland China.

There has also been a rise in anti-mainland Chinese sentiment in Hong Kong in recent years, with people complaining about rude tourists disregarding local norms or driving up the cost of living.

Some young activists have even called for Hong Kong’s independence from China, something that alarms the Beijing government.

Protesters feel the extradition bill, if passed, would bring the territory closer under China’s control.

Hong Kongers know how to protest

In December 2014, as police dismantled what remained of a pro-democracy protest site in central Hong Kong, demonstrators chanted: “We’ll be back.”

The fact that protests have now returned is not necessarily surprising. There’s a rich history of dissent in Hong Kong, stretching back further even than the past few years.

In 1966, demonstrations broke out after the Star Ferry Company decided to increase its fares. The protests escalated into riots, a full curfew was declared and hundreds of troops took to the streets.

Protests have continued since 1997, but now the biggest ones tend to be of a political nature – and bring demonstrators into conflict with mainland China’s position.

While Hong Kongers have a degree of autonomy, they have little liberty in the polls, meaning protests are one of the few ways they can make their opinions heard.

There were large protests in 2003 (up to 500,000 people took to the streets and led to a controversial security bill being scrapped) and annual marches for universal suffrage – as well as memorials to the Tiananmen Square crackdown – are fixtures of the territory’s calendar.

The 2014 demonstrations took place over several weeks and saw Hong Kongers demand the right to elect their own leader. But the so-called Umbrella movement eventually fizzled out with no concessions from Beijing.

(Inputs from BBC)